By Thomas Barrows, MD FACEP

We face plenty of difficulties in running our emergency department. We’re often resource challenged. It’s easy to name off all the things we don’t have: we don’t have an ICU, we don’t have an OR, we usually don’t have OB/GYN coverage, we can’t admit dialysis patients. The list goes on and on.

And however difficult our struggles as providers, many of our patients in Tribal nations face even steeper challenges: poverty, lack of transportation, poor social supports, substance abuse, risk of domestic violence, and food insecurity. They may get their warmth from wood-burning stoves, rather than the central heat and air we take for granted.

This lack of resources made me recall Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in terms of our patients’ resources. And it turns out the basis of Maslow’s opinions has its origins in conversations with Indigenous people.

Western Lens Vs. Cultural Perpetuity

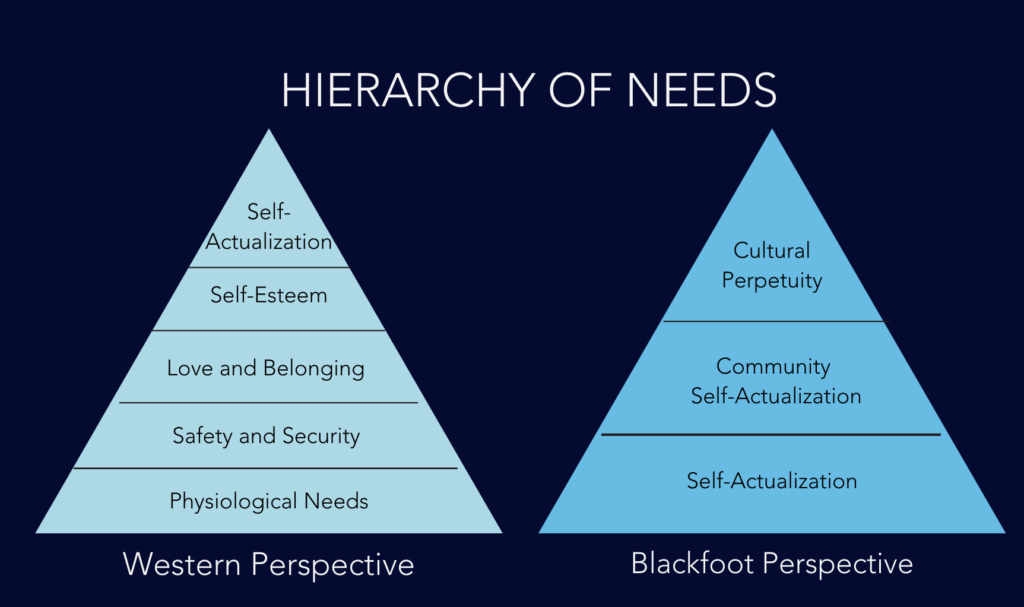

You’ll probably recall learning about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in your basic psychology class. Maslow proposed that human behavior is motivated first by basic needs such as finding food, water, warmth, and shelter before becoming motivated to satisfy safety and psychologic needs. You’ve likely seen the pyramid of Maslow’s Hierarchy.

But I’m guessing most of us didn’t know Maslow conceived of this idea by conversations with the elders of the Blackfoot Nation – or that his “pyramid” was actually meant to be a “tipi.” Maslow visited the Blackfoot back in 1938, the time period in which he developed his theory of hierarchical needs.

However, there’s little scientific evidence to support his hypothesis, in spite of its being taught to students all over the world. In fact, Maslow’s interpretations of what motivated the Blackfoot people appears to be at odds with their own world view. In 2014, University of Alberta professor Dr. Cindy Blackstock presented a First Nations view that was somewhat different than what Maslow believed. She pointed out that “Self-actualization is at the base of the tipi, not at the top, and is the foundation on which community actualization is built. The highest form that a Blackfoot can attain is called ‘cultural perpetuity.’”

Cultural perpetuity is also called “the breath of life.” It is the idea that you will be forgotten but still play a part in ensuring the culture lives on. The chief criticism of Maslow’s ideas is that individual achievement is placed upon the top of the pyramid – as if the Native American viewpoint is flipped to accommodate the western lens.

When Patient Resources Determine Care Outcomes

One of the reasons I’ve been thinking about this topic recently is because of a specific patient deprived of basic resources. Our young patient had been admitted for heart failure multiple times to every major hospital in the state – even some hospitals in other states. The medical service here put a great deal of effort into arranging a visit to the Mayo Clinic for evaluation. Funding, transportation, and appointment dates and times were all set. But the trip fell through because the patient couldn’t afford to stay in a motel.

The pattern of multiple ER visits and local transfers continued until one day the patient had the good fortune to see Dr. Riley in our ER. Dr. Riley picked up the phone to call Mayo and he was able to admit the patient to Mayo directly from our ER. Not only did the transfer take place, but a heart became available during his stay and the patient underwent a successful transplant.

The experience reminded me of the saying “Do the Right Thing at the Right Time with the Right People.”

In another case, a middle-aged man came to our ER with a medical complaint that proved not to be life-threatening. This adult patient had a feeding tube for a remote esophageal injury and a wasted appearance. Although his medical issue was resolved, I asked him where he was staying and who would be his doctor. The patient didn’t know; he admitted he had just been released from the Department of Corrections. He had no money and nowhere to stay. He didn’t know how to get supplies for his feeding tube, his nutritional support, or even pay for his ongoing medical care.

Advocating for Our Patients

We tend to not be very good at these types of problems as providers. They don’t teach us much about dealing with social problems in medical school and we always sort of hope that someone else will sort out these issues for them so we can focus on cracking the mystery of the medical complaint. I’ve learned, however, that none of these things happen automatically, and we need to aggressively advocate for our patients. The ER may be their only point of care.

In the case of the second patient, I did the following:

- I obtained a medical nutrition consult for the patient. The nutritionist was able to provide tubing and other supplies for the patient’s feeding tube, as well as a large supply of Ensure.

- I obtained a social work consult. We arranged shelter accommodation for the patient and transportation.

- I spoke with the business office. They guided the patient toward Medicaid enrollment so that he would have a funding source for ongoing care.

- I made sure he had all his medications that were previously provided by the Department of Corrections and created a follow-up care plan with a medical clinic near the shelter.

Today I make it a point to ask all my patients in the ER one question that ensures we’re really taking care of them and not just one medical issue: “While you are here, is there anything else I can help you with, such as medication refills or any follow up issues?”

It’s amazing how many problems I uncover in asking this simple question. A few recent examples include diabetics who don’t have a working glucometer or supplies, a patient with atrial fibrillation who ran out of their anticoagulation medication, and patients who were supposed to have follow up care for serious medical problems but fell through the cracks.

Expanding the Possibilities of Care

Do you identify more with Maslow’s pyramid or the First Nations tipi? Regardless of your viewpoint, it’s clear we need to consider patient resources and their ability to meet basic needs when we organize their care. Please take a few minutes and ask patients what else you can do to help. It goes a long way.